Ancestors

I don’t know who put together the family tree from 1067 but most seems to be gathered from Brill and Hedgerly Churches. There is also a Crest and Coat of Arms. I was sent a rather sweet illustrated diary which covers significant events in the 19th century. There is also a book on Whitelocke Bulstrode (not a true Bulstrode) who was ambassador to Sweden during the civil war. It is claimed that he changed sides no less than six times and was famed for not so much swimming with the current as galloping with the tide (the Improbable Puritan). Timbrell Bulstrode gained fame for discovering the link between the sewage outfalls in Chichester and typhoid outbreaks caught from the rich oyster beds there. Beatrice Bulstrode was a redoubtable lady who was the first woman to cross the Gobi desert in the 19th century. She was a large lady and when she had trouble with the Mongols, she would grab them by the hair and bang their heads together (so it is said!).

My mother

My mother was the second youngest of four daughters brought up in Newcastle. She studied bacteriology at Durham and met my father, so he says, when he invited her onboard his ship to see a microscope specimen of the syphilis spirochaete. I know nothing of her parents except that her mother was her father’s second wife. I met my grand-mother only once when I was very small. I kept on fidgeting from one foot to the other, and so she was convinced that I needed a pee, and kept on checking.

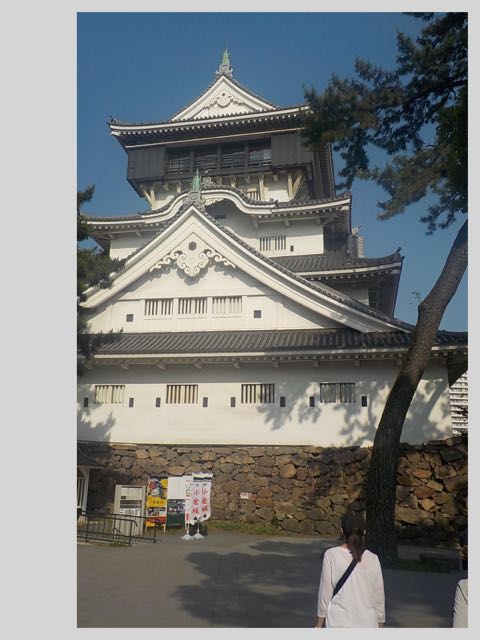

John and Jackie at their wedding

Jackie and Anne – the terrible sisters

Jackie, my mother, was prone to judgements based on pure prejudice and had the temper of the devil too. On one occasion her younger sister Anne had come to stay. They had a love/hate relationship mainly because they were so similar. On the last day of one visit, Jackie had cooked a lobster for a farewell dinner. This was something we never normally ate as it was too expensive. As she was taking it out of the oven Anne came into the kitchen and asked what it was. On being told it was lobster, she said that she did not like lobster.

Jackie and Anne

Without any hesitation Jackie said “You f****** wouldn’t” (dreadful language for those days) and threw the lobster and dish at her. It missed and splattered down the kitchen wall. I stood there stupified (I can only have been six) and then my father’s huge hand firmly grasped the back of my neck as I was propelled out of the kitchen. “You saw nothing” he said“Go to your room!” I did not argue.

Jackie

It is hard to see your own mother in any sort of perspective, but she was certainly capable of great kindness. She was also determined to have her own way, even when she was not sure that it was what she wanted herself. The result was fierce tantrums and her deliberate attempts to confuse love with obedience. She was hugely intelligent, but was frustrated with the life of a mother of three on a remote island in the English Channel. The most hurtful to me (and I suspect the others ) was her inability to praise. So, when I got an open scholarship to University College Oxford to read Medicine, at the age of 16, her only comment was “Well, I have never even heard of that College”

My mother Jackie

As I child I thought that Jackie despised John as she was always saying cruel things to him (and us). Now I am not so sure. Throughout my teens the rows between my mother and I became worse and worse, cruel comments made in the heat of the moment many years before were regurgitated again and again to prove something, I am not sure what. It made for a time of misery, anger, and guilt.

My father

My father, John, was the youngest of five sons, Cuthbert, Bernard, Godfrey, and Martin. His father Ernest was, I think, originally a miller at Brill in Oxfordshire but then moved to Cheam in Surrey. My father told me that Ernest used his carnassial tooth (pre-molar) to check the hardness of the corn and so did not have it removed when it went rotten. Unfortunately this led to cancer of the jaw and so he died young in 1924 when my father was only eight. Cuthbert inherited the mill, Bernard joined the Rhodesian police. Godfrey was in the Kenya Rifles then farmed in western Kenya, Martin became the vicar of Framlingham in Suffolk.

Godfrey with his mother Ethel

The mill was a big business and had Foden steam lorries for delivering the flour. It was taken over by Cuthbert who bankrupted it. He then tried to claim insurance after burning it down and when he was found out, committed suicide. Bernard and Godfey disappeared into the colonies while Martin was a larger than life vicar in Suffolk who was financially supported by my father for much of his life.

John was a kind man. He was also weak (certainly he could not stand up to my mother), but when I saw him for the first time in his white coat working as a radiologist in the hospitaI, I could not believe that this was the same person that I knew from home. In the hospital he was strong and decisive. He had a rule that if any radiology request card came without the word ‘please’ on it, he tore it up. He maintained that there was no reason why courtesy should not prevail whatever else changed. I don’t tear forms up but I do write ‘please’ on them when I write them. This produced a quirky interchange between me and the radiographers when I first arrived in New Zealand. One of them came round to see me to

ask what extra view it was that I was requesting as they couldn’t read my writing. When I explained that it was the word ‘Please’ the radiographer said in good broad New Zealand “Well f**** me, that explains it. We have never seen that word before on a request form before”.

John only got to medical school (Guy’s Hospital) because a friend of the family paid for him, as by then his mother was so poor that she was taking in washing. He then signed up for the Navy at the outbreak of the war having got the conjoint exam from the Apothecaries (the quickest way to a qualification). I once asked him why he volunteered for the Navy, and he simply said that to the young men then, it was simply the biggest rugby match going and that everyone he knew wanted to be involved. He was a good rugby player and represented his medical school, so the metaphor is highly appropriate.

My father, John

After the war he trained as a radiologist, and after a couple of years was summoned by the Professor who, in those days, handed out consultant jobs when it was felt that ‘You were ready’. He was offered Balham in South London, or Guernsey. He was told to talk it over with his wife that night and then bring his answer in the morning. He had no idea what Guernsey was like, but they both knew that they did not want to spend the rest of their lives in South London. And so he became the sole radiologist on the island of Guernsey for the whole of his career. That was how jobs were organized in those days. No advertisement, application, short-list, or interview, just a benign dictator placing people where he thought they would do best. Of course, it encouraged the rankest form of nepotism but probably minimized the terrible stress that our generation experienced trying to find a consultant job.

At first, my father had what is called a good war, nothing exciting. He played endless games of bridge with a colleague who went on to become a professional bridge player. He then volunteered to join a friend appointed to a mine sweeper in the Mediterranean. The ship

was torpedoed by a German submarine that they were hunting, and the ship capsized as she sank. Half the crew were in the water on one side of the boat and half the other when the depth charges loaded and primed on the afterdeck exploded. All those on the wrong side of the ship were killed. Nothing would persuade my father to talk about this devastating event but after his death, I found a short autobiography that he had written and which I am incorporating into this document.

He was a Freemason and assured me that all the important political decisions about how the hospital should be run in Guernsey were made at the Lodge. He tried to persuade me to become a Mason too and was mortified at my scathing criticism of secret societies. As young child, he would never tell us where he was going on these evenings out, just that he was going ‘brick-laying’. He always had a bath before he went out and there we could hear him practicing his ‘lines’. We would stand outside the bathroom door chanting “Our father which art in the bath”. He would bellow from inside “Go away, I am doing secret things”, so there was at least some humor to the situation.

Martin Bulstrode (John’s older brother – vicar of Framlingham)

The Foden Steam lorries at Great Grandfather Bulstrode’s mill in Wandsworth

The sofa table

He also made a beautiful Queen Anne sofa table at carpentry classes that he attended once a week for over ten years. It is a true master-piece, and took over 18 months just to polish. I would love to have created such a master-piece and certainly it gave him great pride.

He taught me one important lesson late in life. Just before he died he quietly told me that all he wanted to do was to die with dignity: nothing else mattered. I think for his generation, and maybe even for ours, appearances matter a great deal more than we care to admit.

As we children got older Jackie’s passion for organising the Pony Club became all consuming so that slowly he gave up his boating and focused on helping organise Gymkhanas. I think he was sad about having to give up his boating, but was proud of his chapter in Adlard Coles “Channel Harbours and Anchorages’ which covered Guernsey, Herm and Sark.

Guernsey, Society

Les Mourants

In Guernsey, where we had moved when I was two years old, we had first rented an ugly brick house called Jardin Cluet which I don’t remember at all, although it was always pointed out to me as a child. I always felt slightly uncomfortable that I had lived somewhere which I could not remember.

We then moved to a lovely traditional granite house called ‘Les Mourants’ with a garden, four greenhouses and a substantial barn. It was cold. Life in the winter revolved around the Aga stove in the kitchen and the fire in the living room.

Les Mourants from the road

The first noise in the morning was the sound of my father riddling the grate, and then the swoosh of coal as the Aga was refilled with coke. There was no double glazing, and the sash windows rattled in the wind as they leaked cold air around their frames. We children would sit crouched against the side of the Aga or fighting to get closer to the open coal fire in the living room. Either way the zone of warmth was very small indeed, and the rest of the time we were cold. Getting into bed was agony and the only way to warm up was to curl in a ball under the blankets and try to direct your warm breath onto your feet.

We first got a black and white television when I was eight. There was a terrifying science fiction serial called ‘Quatermass and the Pit’ which had me whimpering behind the sofa. Otherwise there were just board games like Monopoly but Jane and I used to fight over them and I certainly remember my father throwing one set into the fire in exasperation at our behaviour. I found reading very difficult and preferred books with lots of pictures.

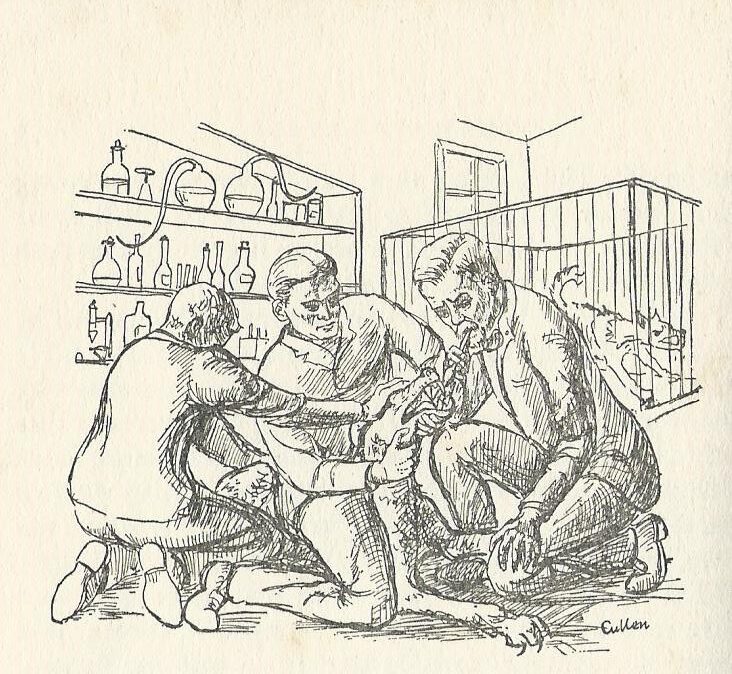

Rabies

One terrifying book was a life of Louis Pasteur. In it there was a vivid pen and ink sketch of a boy being bitten by a rabid dog. For whatever reason I was already terrified of dogs and this gory story was the final straw.

From then on I was convinced that there was a rabid dog under my bed and that the only way that I could safely get into bed was to run as fast as I could across the room and leap high onto my bed and get under the bedclothes as quickly as possible. The crash as I hit the bed drove my parents mad, but they did not understand, I had no choice.

Guernsey

Guernsey was a very small rural community then. The farmer’s fields were tiny and scattered all around the island because the Napoleonic laws of inheritance required that farm land was split equally between the children. The result was a patch work of fragmented, and hopelessly uneconomic farms on which cows were kept for milk, while daffodils and potatoes were grown in the spring. There were very few trees in the 1950s. I suppose that most had been cut down for fire-wood during the German occupation, but there was a lovely stand of Elms straight across from our house, which roared when the gales blew from the West. These days the island has a much better cover of trees, but those Elms have all gone, smitten by disease. However, what the island lacked in trees it made up for in high banked hedges lining every small field and lane. In spring they were coated in violets, and primroses. In summer the gorse glowed yellow while the seed pods popped, and filled the lanes with their cloying scent. In autumn delicious blackberries tainted with salt could be found hiding in amongst the bracken stalks. The local farm and the lanes around it was a great playground for a child. It surprises me now how big it all felt then but what a small range of fields I actually knew. What seemed miles from home, is now, I find, only a couple of hundred yards away from our gate.

Society in Guernsey

The island of Guernsey was divided socially into three groups: locals, rentiers, and visitors. Rentiers were those who did not belong on the island but had come more recently to evade death duties etc. They were only allowed to buy certain houses which were said to be on the ‘open’ market (rather than the local market). These houses were bought for vast sums, done up, and then occupied by wealthy old people waiting to die.For the Rentiers, Guernsey was a retirement home by the sea that imported gin and exported empties.

For the visitors, it was a classic bucket and spade holiday with boats that took them to the off-lying islands of Herm and Sark and even a boat that took them down the East Coast of the island to a lovely inaccessible bay called Fermain.

The locals were basic Brittany peasant stock either tending tiny farms or fishing the local waters.For the locals there were some darker stories to cover-up. It appears that most locals collaborated with the German occupying force during the Second World War. They had little choice. But, some did not, probably far fewer than claimed to have resisted later. There was great bitterness about who had and who had not collaborated. It is said that the local girls who went out with Germans were tarred and feathered at the end of the war. Now no one wanted to talk about it.

By all accounts, the locals were quite well treated, but Russian slaves were brought in to build gun emplacements and even an underground hospital. The cost must have been quite phenomenal. These fortifications were built on top of the old granite Martello towers erected in the Napoleonic war to protect the islands from invasion by the French and blighted every beach and cliff view in the island.

In the ruins near the cliffs on the east side of the island, there were buildings with pipe outlets all along the walls. Were they the remains of the gas chambers on the island? I am not sure but I do know that none of the forced labour brought to build the huge fortifications there left the islands alive.

Tomatoes

Next door to us on one side was a tomato grower, Mr Roberts, and on the other a farmer Mr Browning with two boys the same age as Jane and myself. Mr Roberts was a bachelor with (quite literally) green fingers, as for 355 days of the year he was up and down working in his huge greenhouses. Mr Roberts grew tomatoes and sometimes flowers: irises, and freesias. The key to profit was getting them to market early, and so the plants were grown under glass which were heated by coal boilers. These pumped hot water through large cast iron pipes set between the rows of plants. In the autumn steamer boilers were towed to each vinery in turn. The plants were up-rooted and the soil dug up. Then thin pipes were inserted through which steam was injected to sterilise the soil and kill all spores. The whole island smelt of coal and steamed soil for those months. Then in the spring, the acrid back-of-the-throat smell of coal started again as the growers heated their vineries to ‘force’ the tomatoes. It must have been an expensive business and tomatoes were only worth harvesting early in the season. Later on, cheaper tomatoes could be obtained from open-air farms. I just remember how hard work it all seemed. The soil had to be dug by hand to insert the pipes. The boilers had to be stoked and filled with coal by hand. The sterilizing pipes all had to be manhandled into place. Then the tomatoes had to be laid carefully into wooden boxes and the lids nailed down before they could be shipped to Covent Garden.

In the summer as soon as the price had glutted the tomatoes were dumped, and then we would hide behind the hedge by the road, mortaring cars coming past with over-ripe tomatoes. Mr Roberts then vanished for ten days to Cannes (which he called Canes) where he stayed at the same casino every year and gambled his profits away. When he returned, the greenhouses were dug over and the season started again. Once air freight started from Spain and the Canaries the whole early tomato industry collapsed and the lovely long wooden framed greenhouses all started to fall down. Between them in the narrow fields, daffodils were grown for the flower market. Once again that business was overtaken by early flowers from Holland. As soon as the flowers were over, the cows were put in to graze the grass and the daffodil leaves. For a few weeks, the milk had this strange taste brought on by the cows eating the daffodils.

In the middle of the summer, there were a series of Agricultural shows where huge floats made of flowers paraded around and were judged by the visitors. My mother made us take part on our horses parading in fancy dresses. These shows were called “The Battle of Flowers” I don’t know why, since as far as I know, there was no battle, but the visitors loved the show.

The Farm

The farm next door was a magnet. There was always something interesting going on there. There were fields with rabbits in the hedges, and flooded meadows where the stream ran through the farm. There were hay barns to hide in, and outlying fields to visit riding on the bars at the back of the tractor. Looking back I realize that the farm was terribly run down, with caved-in pig-styes and rusty corrugated iron sheds. But the farmer was kind, and there was always something to do.

Toothless with my sister Jane

Guernsey Bulls

The fields were so small and the grass so precious that the cows were always tethered by a short chain to a stake hammered into grass. They could only graze within that circle, and then at the end of the day they would be brought in for milking. The following day the stake would be moved to a new patch of ungrazed grass. The farm bull had an extra long stake, and we knew quite well that if the mood took him he could pull that stake up and then it was ‘to the trees’ for us. The bulls were normally very docile but Mr Browning warned us that many a farmer had been gored from turning his back on a ‘docile’ bull. He told us that it could happen ‘any day’ and frightened us witless with stories of the how the bulls kneel on their victims after goring them with their horns. The cows and bull were kept stabled all winter presumably to protect the ground from being cut up, as the grass actually grew all the year round in that gentle climate. When the bull came out for the first time in the spring he was very belligerent, and I remember Mr Browning standing four square with the big wooden mallet he used to drive in the tethering stakes. As the bull snorted ready to charge he stepped forward and struck him a mighty blow with the mallet between his horns. This seemed to settle the bull for a couple of minutes while he was led on up into the field. Then, as soon as he turned his back the bull would start snorting and pawing the ground again. Mr. Browning used to curse each time the bull played up. His favorite oath was “Hell’s Bells, buckets of blood!”. We thought that was a marvelous oath.

One day we children were playing rounders in the lower meadow where the bull was tethered. A beautiful strike (not by me) lofted the ball, which then struck the bull on the side with a solid thwack. None of us waited to see the consequences. We all ran for our lives and climbed the nearest tree. When the dust had settled we finally retrieved our ball. It was bitten and chewed and soaked in saliva. We stood in awe imagining how we would have felt if we had been that ball.

I suppose that Mr Bowning’s farm was modern for the 1950s. He had one small tractor, a plow, a buckrake, a hay cutter, a tedder, and a trailer: that was about it. For us kids the best fun was tunnelling in the hay rick, quite a dangerous past-time if the bales collapsed, but wildly exciting for us. The yard was full of chickens and was the centre of a game called ‘Kick the Can’. The person who was ‘It’ stood in the centre of the yard guarding a tin can, while the rest of us hid as near to the can as we could. As soon as the game started the search for the hiders would start, but if the ‘It’ got too far from the can, a bold hider could break cover, run in and kick the can as far away as possible. During that time everyone including those who had been found and captured could run and hide again.

That farm seems tiny now, it cannot have been more than 10 acres, but then it seemed a whole world to range in, with streams, cliffs, valleys, and even the odd tree to climb. Farming must have been heavily subsidized as there is no way that a family could make a living from such a small area of poor land.

Before I was sent away to boarding school the children on the next door farm were good friends. But once I had been sent to ‘away’ everything changed and I felt an iron curtain come down between us. I wonder whether it was me or them. How can you know at that age?

The Neighbourhood

Just up the road from us half a mile away was the German Underground Hospital, a set of tunnels driven into the granite walls of the valley that had housed a hospital during the German occupation in the Second World War. The main part was a tourist attraction and we certainly could not afford to go there, but there were other unsafe partially flooded tunnels and we could slip though the wire into these. The echoes were wonderful but we were assured terrible punishments if we were caught there.

Directly over Les Mourants, the planes came in on the final flight path to the airport. First, it was biplanes (Rapides) then Dakotas, and finally Viscount turbo-props and Handley-Page Heralds. The airport was often closed with fog and/or wind and then the island felt very cut off, as the ferry only came once a week in the winter.

Tourism

The island relied on the tourist industry in the summer. The ferries to Guernsey and Jersey were owned by British Rail and every employee and their family of this huge organisation had one free rail pass anywhere in the UK once a year. As the Channel Islands was the furthest point on British Rail and there were duty-free cigarettes and alcohol, a substantial proportion of BR employees took their annual holidays in the Channel Islands. When Beeching sold off the ferries as part of the re-organization of the railways, the poor company taking them over appeared not to realize where all the business was coming from and promptly went bankrupt. So the shipping line and the tourist industry all collapsed together just as the tomato and flower growing business were overtaken by warmer climes and more efficient production in Europe.

However, the islands were already starting to change as large numbers of elderly British, from the ‘mainland’, as we called it, came to retire and die there surrounded by their money. They were followed by the offshore banks whose brass plates litter the walls of the granite buildings in St. Peter Port. From a horticultural and tourist based economy, the islands have become reliant on off-shore banking or swindling as it might be better described. Apparently, the British Government tolerates it because they would rather it went on where a close eye can be kept on it, than in some remote archipelago where it would be mixed with drug running and money laundering.

Superstition

Then there was superstition! One day when I was six I was fiddling with my penknife (we all carried knives) I cut myself in the web of my hand between the thumb and index finger. All the other children in the playground gathered round for a glimpse of blood and gore. One of the girls said that her grandmother had told her that if you got a cut between the thumb and finger, you would shortly die of lock-jaw. She went on to describe the symptoms of Tetanus in gruesome detail as only a young girl could. My heart froze within me and without further ado, I set off and ran the two miles home weeping all the way, convinced that my death, a horrible one, was nigh. Now if I ask medical students if they were ever told this story in the playground, about 20% say that they have, but there doesn’t seem to be any regional bias to the distribution of this playground superstition.

I do wonder how many ‘old wives tales’ affect our thinking consciously or unconsciously. The idea of ‘catching a chill’ from getting cold is patently nonsense, so is the idea that reading in poor light damages your eyes. And what about “If you make that silly face and the wind changes, you will be stuck with it!”. Of course growing up as a child you take all this for granted. As we walked past the local church we were always taught to say “Bon Jour, Grand-Mere” to the statue which made up the gate post. For good luck we would lay a coin or a flower on the top of the stone. Many years later I was showing a visitor around the prettier parts of the island and mentioned this custom that we had been taught. As I told the story I ran my hand across the top of the stone, and damn me there was a fresh violet which must have just be put there. When Enoch Powell (a notable right-wing politician and expert on old churches) visited the island he recognized the postern as being a pre-Christian Druid statue long-stone which in Celtic or Roman times had breasts carved on it and was then be incorporated into the ‘new’ church to link the old with the new, a classic example of syncretism. He went further and explained that the stones were usually found in pairs and that the second stone was often built into the base of the church tower, facing inwards. The group with him went to look and sure enough there was the second statue. Despite his dreadful fascist politics, he rose in my estimation a lot after that. It was only many years later that I was part of a demonstration outside Oxford Town Hall when Enoch came to speak. It was a jolly demonstration and quite valueless. We blocaded the front door, and he was smuggled in the back. At an especially excitable moment one of the students bagged a policeman’s helmet while his arms were locked into his colleagues so that they could hold the line. We were jubilant until a senior officer climbed the steps and very politely asked us if we would give it back as otherwise the officer would have to pay for a replacement himself. We talked about this and agreed that the proletariat revolution would not want one of our ‘brothers’ to suffer, so we handed it back.

The West coast of Guernsey (indeed all the Channel Islands) were important to the Druids so there were quite a few Dolman burial sites. On the Southwest corner of Guernsey at a place called Pleimont, there was a ring of stones with a well dug out circular trench around them. This was called the fairy ring and we children used to run around it as fast as we could. Later on one of the girls from a Guernsey family told me that she had been brought there at puberty and made to dance around the circle at the full moon so that her fertility would be improved. I have to say that her fertility was certainly not foremost in her or my mind while we were having this discussion in the back of a car.

I think the superstition remains that you may drown with stomach cramps if you swim within an hour of eating. It was thought that all your blood would be diverted to your bowel from your muscles and so starve them of oxygen. Whoever thought of that? My childhood was blighted by a mother who kept feeding me. Just as my hour was nearly up so I could go swimming my mother would give me something to eat and the clock started again.

Fishing in Guernsey

My father taught me trout fishing. He belonged to a club that fished on the reservoir in Guernsey. It was a very peaceful place with lots of wildlife (for Guernsey) and frankly, I just loved going there for the peace and because my father was so keen for me to do it. He would be so pleased when he got home from work to find the rods ready on the car. It was also an occupation where we did not have to talk as it was talking (with me) that seemed to worry him a lot. His day’s work was so remote from what we do now that it is hard to imagine. At ten to nine in the morning, he would leave in his car for the 1.5-mile journey to the hospital where he had his own reserved car parking space. At 12.30 exactly he would arrive home for lunch. His briefcase contained the Daily Telegraph and the cross-word had always been finished. At 2 pm he drove back to the hospital and then at ten past five he was home for the day. He never got called out at night, and he never worked weekends. A locum was brought in for his annual holiday. What a different life we consultants live today.

Swimming, Boats and Herm

Clothes

Clothing in Guernsey was simple for me before I started school. In summer it was canvas shorts, a canvas shirt, one set of red and one of blue. Once a week my clothes were removed, boiled and replaced by the other set. In winter it was gumboots without socks, and in summer no shoes at all. Your feet hardened up pretty quickly, and the only time I was cold was when I went swimming in the sea. My sisters seemed able to stay in the water for hours. For me, it was minutes and then I was chilled to the bone. At that time there were no wet suits, so when my father went spearfishing he would wear an old Guernsey and a pair of flannel trousers. There was something rather quaint about a fully clothed man waddling into the sea with flippers on.

Swimming

Swimming was the most frightening (and therefore fascinating) thing to me as a child. I know, because my nightmares were full of it. Not only was I bitterly cold but I was also very scared of swimming in the sea and yet could not resist trying it.

Freezing as usual

At the North end of the island there was a beach called Portinfer (Devil’s harbour would I suppose be an apt translation). It was only good for surfing at low tide when a strip of sand was exposed. At any other stage of the tide the waves broke in over rocks and swimming was impossible. Then long hours were spent above the high tide mark where, if the sun was shining, the sand became quite hot and lovely to lie on. It faced the prevailing wind from the West so must have been useless as a harbour but excellent for body surfing. The problem was the undertow, a savage sucking current that seemed to drag you down and out, each time a wave broke. We surfed with small sheets of plywood which had a slightly upward curved nose. Even so, they had a nasty habit of nose-diving as you came down the breaking wave. The front would dig into the sand and you would be punched in the solar plexus by the back-end of the board. The result was that you were winded and buried in the foam from the breaking wave, unable to breathe. This was an agony only matched by the horrors of whooping cough.

At half-tide lots of rock-pools became exposed, inhabited by small but greedy little fish and equally ravenous crabs. A small hook with a bit of limpet as bait never failed to catch one or the other. The crabs were then carried off to put in the girl’s swimming bags.

Rock-pooling

Boating

My father loved boats and everything about them. He had crewed in the Fastnet race as a medical student and had obviously loved his time in the Navy up until the moment they were sunk. His language was peppered with nautical phrases. He had a motor-boat called Moulinet. She was an elegant 26 footer built of pine on oak frames.

Moulinet in St. Peter Port Harbour

Technically she could sleep two and initially had a methylated spirits stove, which was then replaced by gas where he could brew up tea. Her engines were typical 900cc Morris 1000 engines adapted for Marine use. To start them they needed petrol, but once running and warmed up they could be switched over to run on paraffin which was cheaper and safer. They were devils to start on the crank handle and required continuous tinkering from my father who loved those engines dearly. The cover over them in the cockpit was warm, and I was invariably cold, so my favourite spot on the boat was to curl up on them and hum tunes to myself. The vibration of the engines made it easy to hum in tune, as I am completely tone deaf. When I was young we seemed to be out in the boat all the time, and my father loved to teach me all the nautical knots and terms. He obviously missed his time in the Navy and had clearly enjoyed all its traditions. Whenever a naval ship visited he insisted on sailing out and dipping his ensign so that they were obliged to dip their ensign back in return. What a bloody nuisance for them, but what pleasure it gave him. My mother hated boats with a passion, so there must have been some tension there. She would block outings in the boat for all but the mildest weather and insisted that we had a motor boat with twin engines and no sails as safety had to be paramount.

Moulinet towing her own tender (Winkle) and the Duckling sailing dinghy back from Herm

My father was fascinated by inshore navigation and ended up writing the chapter on the Channel Islands in the definitive book Adlard Coles’ ‘Channel Harbours and anchorages’. So, every voyage in Moulinet was a major navigational exercise with charts, forward and back marks, and the setting of tides. I was fascinated.

Herm at high(yellow) and low (blue and green) water

The chore was preparing the boats in winter. I have never been good at painting, I have not got the patience, but wooden boats of all things need great attention to detail if they are to look half reasonable. I would always start off with the best of intentions and then things would slide downhill from there. When my father stored the boat in the yard at the harbor, there were a group of like-minded buffers with similar boats stored there. They had ladders up the sides to get on board and were continually inviting each other for brews of tea, while they discussed the problems of boat maintenance.

Horses

Later my mother and sisters became interested in riding and we acquired three horses. Riding came to dominate our lives and boating became less and less and important. I think they always realised that my heart lay with boats, but my father was committed to helping with the Pony Club, so boating became a rare event.

My boats

My first boats were blocks of wood with a nail on the front to which I attached a string. They were towed everywhere by me, behind Moulinet, and behind me over land, until the string snapped and they were lost. When I was sent away to boarding school at 8 years old we had to take a model boat with us, and I was allowed to choose mine. She was a gorgeous Bermuda-rigged yacht with a lead keel. I adored that boat. My little sister has it now. I wonder if she realizes how much it meant to me. I hope so. It felt like my only link with home when I was sent away. You could trim the jib and main so that she sailed in a straight line across the swimming pool at school. She did not have a rudder-like the more expensive boats that many of the other boys had, but in my eyes, she was quite the loveliest on the lake and even looked good when she broached, which she often did.

My second boat was a red balsa wood catamaran that my father made me for Christmas. Jane had a varnished one, and both had clearly been finished in a hurry as they smelt strongly of paint. We sailed them on the model yacht pond in St. Peter Port. They were fast but never captured my heart like my Ailsa yacht.

Moulinet had a tender (a clinker-laid wooden dinghy called Winkle) which my father converted into a lovely little sailing dinghy for me, with a balanced lug-sail

Winkle working for her living – Jane rowing

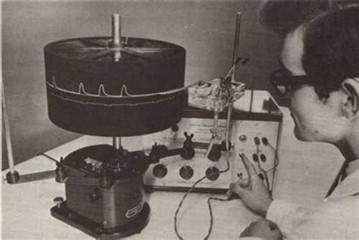

It was real Swallows and Amazons stuff except that there were no swallows or amazons to play with. My sisters rode horses and once I was sent away to boarding school friends were few and far between. Sailing a boat alone did nothing for me, and I had no interest in racing. Winkle was quickly replaced by a lighter and better rigged ‘Duckling’ dinghy which I was allowed to sail around inside the harbour. Later, much later, I bought a small catamaran, a Swift called Mpaka (the Swahili for swift).

Mpaka

It had belonged to Tim Barton, Jane’s future husband and he now had the larger and much faster Shearwater catamaran called Haraka (fast one) which I admired unreservedly from afar. I had never imagined that a boat could sail so fast. My Swift was only 14 feet long but Tim’s Haraka must have been over 16 feet and seemed enormous to me. He could sail to the island of Herm over 3 miles away in what seemed like only minutes.

Even now, if I want to get to sleep I have only to imagine that I am turning a boat away from the shore, hopping over the gunwhale and sheeting in the mainsail and I am asleep. However, racing is a different matter. It seems to me to be the antithesis of everything I love about sailing. I will race with Simon because it obviously gives him such huge pleasure, but I would much prefer to settle down and feel the boat going well, than to fret whether we are beating the others or not. Give me a windsurfer and I will go as fast as I can, but try and beat someone – never. It is probably sour grapes because so many of my friends and relatives are such good sailors that I would never be able to beat them anyway, however hard I tried.

Peter Heyworths Irriquois cruising catamaran. She was really fast Helming

My other passion as a child was sitting on an inflatable airbed (a Lilo) and paddling round the rocky inlets of the bays on the east side of Guernsey. The tiny airbed was a virtually indestructable canoe and the worst that could happen was a dunking after being rolled by a breaking wave. But the fun and sense of adventure of creeping up the narrow gaps in the granite cliffs where the waves roll you in, then suck you back out again, was a real joy to me.

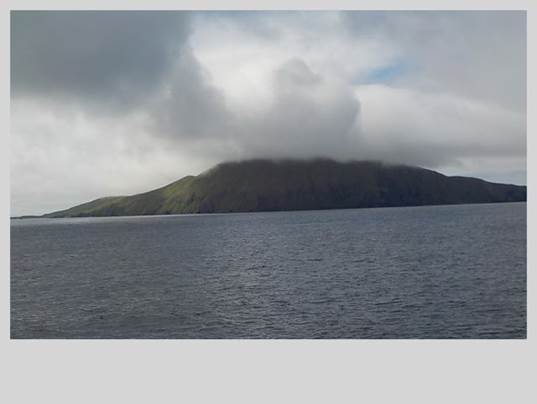

Herm

Herm was a dream island, only a short distance from St. Peter Port and surrounded by reefs, strong currents, and huge areas of sand which were exposed at low tide.

Shell beach at the North End of Herm with Sark in the background. A wonderful paradice of currents, rocks and huge tides

Each side had different challenges and just beyond it between Herm and Sark was the Petit Bouillon an area of swirling whirl-pools where the tide ripped around the island. This place filled me with a mixture of fascination and fear. The deep swirling currents – would they suck you down if you tried to swim there? Who knew? The island was small – only a mile or so long. Walking along the paths on a hot summers day nearly burnt your feet. To the North were sand dunes: to the east was a wonderful beach with sand eels which could be netted and cooked over a fire.

Barbecue on the beach in Herm

To the south were cliffs with a blow-hole in them which had been literally blown apart in a storm, and on the west side was a small harbour which dried out at low tide. Just south of it was an area – Rosaire steps – which at high water looked like a series of rocks, but as the tide fell it became a lagoon protected from wind and tide where we could play.

It was there that my parents organised a party with a barbecue of grilled sausages and a proper sea-battle between the dinghies of the various boat owners. We loaded our dinghies with plastic bags filled with water, irrigation syringes from the garden and went to war. It was the most delightful fun, except that I think that the anticipation of the event was even more fun than the event itself.

Herm presented my father with a navigational challenge which clearly gave him huge pleasure. Our small boat would have to weave between the rocks with evocative names like Anfre and the Creux, swept by the strong currents which pass between the islands.

At the North End of the island there was a lovely sandy beach where my mother could sunbathe and gossip while my father hunted for mullet and bass with a speargun, brewed tea and tinkered with the engines.

Long Beach -towards the North of Herm Island

My father’s finest catch with a spear gun off Long Beach

There was a strong current running along that beach. It then swept round a small rock promontory and out to sea where the end of the island curved away. I lived in terror of being swept away by that current, and the corner around the rock was where I knew that, beyond that point, there would be no hope whatsoever of saving me. I had nightmare after nightmare about that rock outcrop. In fact the beach on the other side of the outcrop was lovely. The high tide mark was coated with tiny cowrie shells and there were the collapsed stones of a Dolmen burial site right at the end, so my fears were probably completely unfounded. Beyond that beach, and around the corner were high sand dunes with hot sandy slopes. You could run along the grassy top and hurl yourself outwards into the air, landing far below in swirl of steep sloping sand. Except that it was not grass on top. The ground was coated with spiky Marram grass and a small yellow sand rose with vicious thorns. So, the run to the edge was always tinged with a volley of agonising pricks to the soles of your feet.

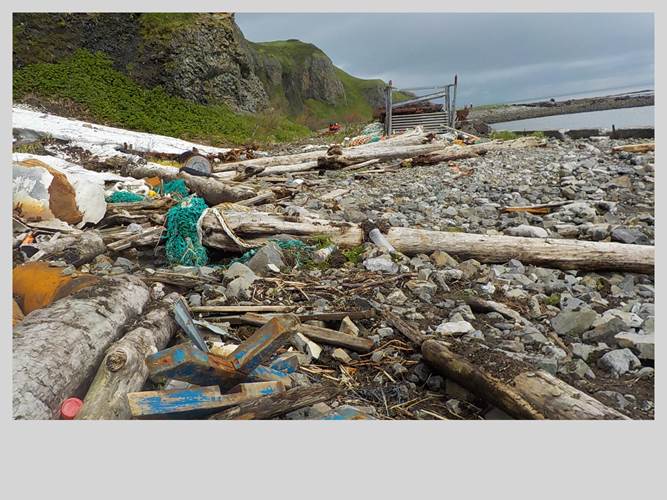

The Humps

Out beyond that north facing beach there were large reefs which at high water appeared as solitary rocks foaming in the rip tide. But at low water the island of Herm doubles in size and a whole world of sand dunes, rock pools, and rocky reefs, looking like mountain ranges, appears. I was fascinated by this conversion every tide from a few solitary rocks to a whole new unexplored world, which had the added attraction of a crashed second world war plane tucked in amongst the rocks.

The Humps at low water springs

On rare days the tides and the weather were right, and my father would take the boat gingerly around that north end of Herm and out to a great sand bar called ‘The Humps’. When we arrived there just after high water it looked as if we were anchoring in the open sea with a few scattered rocks peeping out around us. As the tide fell a whole new country would appear until we were completely surrounded by sand banks, left floating in a small placid lagoon. To me, this was heaven. My passion was to make model boats out of a piece of wood. In truth, these were just blocks of 2 x 1 with one end cut to a V shape to make a bow. I was allowed to tow these behind the boat as we headed for Herm, but woe betide me if the string broke, or the knot that I had used to attach it came undone. My father would rarely turn back to rescue them and I was miserable when a well-loved boat bobbed away into the distance. However, once out at ‘The Humps’ there was a whole new uncharted land to discover. My boat would be towed up rapids, portaged across sand banks and traverse new ponds (lakes). It was a time of utter contentment, alone with my dreams and imagination. The end of those days was even more miraculous. Throughout the ebb and start of the flood, our placid anchorage would be surrounded by the roar of the tide cutting each side of the Humps. As the tide rose the Humps would vanish and then we were at sea again, as if the whole day had been a dream.

Exploring Guernsey

My adventures with model boats took me to streams on the main island of Guernsey and far further afield than I had ever been before. My bicycle became a wonderful means of escape, but I also used it to ride to school. This ride, when I was seven, must have been around 2 miles and I did this journey every day unsupervised. What freedom! It would be against the law now, but it must have given my mother a blessed release from the interminable school run.

Schools

Blanchelande

My first school was a catholic convent and I was clearly not welcome. Coming from a non-religious family the nuns regarded me as some sort of infidel. I remember being sprinkled with salt in an attempt to purify me! I also remember being taught about mortal and venal sins, and being warned that already I was doomed to a substantial time in purgatory for talking too much. My fascination with astronomy at that time became very tangled with all this high church clap-trap. I was convinced that Venus and Venal had the same derivation and that therefore my extensive sentence in purgatory would be spent on Venus. My astronomy book had an especially vivid artist’s impression of the surface of Venus; rocks and sand – emptiness. Many an evening reading in bed was spent speculating on what I would find to do in this empty but rather exciting-looking place.

When we were all given luminous (and radioactive) models of the Virgin Mary to put by our beds, my father, a radiologist finally lost his cool. He was not having us exposed to unnecessary radiation in the cause of a superstition-riddled religion, so we were removed from the school.

Blanchelande College

The Monnaie

I was then sent to a small school run by a missionary who had returned from India. Well, it certainly wasn’t ‘out of the frying pan into the fire’. He was a gentle and kind man who was a quite inspirational teacher. He seemed to understand children and their world of adventure and imagination. He filled us with Rudyard Kipling-esque stories of his time in India. I was mesmerised. When I was summoned to his study having been reported by some busy-body lady for pedalling my bicycle to school while going DOWNHILL, he frightened the beejeejus out of me by describing in graphic detail the death of a boy my age in India who had done that very thing and crashed.

Hopscotch

In the playground we learnt hop-scotch, and British bulldog. Hop-scotch seemed to appeal more to the girls. It involved throwing a pebble into a square then the rapid repetition of a complex set of what were really dance moves, as you hopped across squares chalked on the ground. You were not allowed to touch the lines or fall over. I am sad that I never see a hopscotch pitch drawn out on the pavement anymore. I would not be able to resist trying that hop-hop-split-hop-split-hop-hop and turn, hop-hop-split-hop-split-hop-hop and home.

Hopscotch pitch

British Bulldog

British bulldog was much more the boy’s cup-of-tea, with the brilliant fast chases and captures. It needed a pitch at least the size of a tennis court. The ‘catcher’ guarded the midline of the pitch, while all the rest tried to cross from one back line to the other without being caught (touched) by the catcher. As soon as you were caught, then you became another catcher. At each sweep from one end of the court to the other, there were more catchers and fewer players until only one (the winner) was left.

Cheam

I suppose that I must have been bright because the headmaster told my father when I was just eight that there was nothing more he could teach me and that I should be sent away to boarding school, having already sat and passed the eleven plus. My father says he was convinced that I should go to a main line boarding school so that I would meet the right people, and be able to get a job in the city even if I was stupid. He also wanted me to be at least competent in every sport so that I would not let myself down if invited to ‘week-ends in the country’. I realise now that this all relates to his upbringing in the Edwardian era, but he was right to get me out of the islands as I would have been big trouble there as a teenager. However, I wonder how many children took this transition of being sent away to school easily. For me it was the end of a world in the islands. I don’t remember wearing socks or vests before I went away to boarding school. Buying all the uniform was a horrifying business. It all arrived from Harrods and was much too large. I can remember the smell of it now, newly pressed flannel, and the claustrophobic sense of wearing a tie, vests, pants and shoes. The other problem that I discovered on arrival in the mainland was that I had no concept of money. If I wanted something in Guernsey I went in to a shop and asked for it to be put on my father’s account. If he didn’t have an account at that shop then they opened one there and then; they all knew my father. I must have sounded like royalty when I got to boarding school.

Cheam School

Suddenly it was time to go. Today, I realise that it is worse for those staying behind but at that moment I just felt abandoned. There were four of us all going to the same school, and we were ushered onto the biplane (a Rapide) with our large ‘Unaccompanied minors’ badges dangling round our necks.

De Haviland Rapide

Dakota DC3

For the start of my first term my parents and sister came over and we all went to London to see the sights. I had read somewhere that ‘the streets of London were paved in gold’, and had my new penknife at the ready to gouge any pieces out that I could find. There were indeed flecks of something shiny in the pavements and as I dawdled along trying to decide which one to dig at, my older sister Jane asked me what I was doing. To my everlasting mortification I explained my plan to her. She thought this was the funniest thing she had ever heard. My inability to distinguish metaphor from fact gave her something to tease me about incessantly for the next days, until I was almost glad to be going away to school.

Scrum half in rugby – I loved it but my parents never came once to watch

While I was away both my father and mother wrote every single week. What a labour of love that must have been. I wonder if they realised how important that contact was.

Leaving Cheam for Radley aged 12

Prince Charles

Prince Charles started at Cheam the year before me, so we had detectives around the grounds day and night. They were lovely to talk to, showed us their pistols, and even gave us a demonstration of how the dogs worked. I had nothing to do with Charles himself. Any difference of age is a yawning gap of maturity at that stage and anyhow he had his own circle of friends. However, on Father’s Day Prince Philip came down to play cricket. We were not remotely interested in him except that he arrived in a brand new black Sunbeam Tiger sports car which he parked right on the boundary with the other dads who had smart cars to show off. No, the interest for us was Edrich’s dad John Edrich, a test match cricketer, and therefore an absolute hero of ours. When he came in to bat his first shot was a tidy forward defensive. But his next was a beautiful off drive taken on the volley and driven effortlessly to the boundary. This is what we had come to watch. The ball lifted and lifted and then dropped in a soft parabola until it landed with a smack on the bonnet of Prince Philip’s new car, caving it in. You could have heard a pin drop around the ground. Nothing was said then, but at the prize-giving Prince Philip gave out all the awards and then stopped, stood up straight, slapped his hands behind his back, and turned glowering towards the Head Master. “Now then,” he said “About that car!’ He paused for what seemed like an eternity then continued “…….What am I going to tell the wife?” It was a lovely moment, a witty remark, and perfect timing.

I met Charles again fifty-five years later when he presented me with the CBE. As you step forward to receive your award, his aide de camp whispers in his ear, priming him on what to say. I was duly congratulated on my humanitarian work. You are not supposed to speak, but I could not resist reminding him that the last time we had met was when he hid behind me in Geography classes at Cheam, leaving me to the wrath of the redoubtable Colonel Shipway, who taught Geography and the History of the Empire, punctuated by loud blows on the floor from his pointer. For a moment Charles was non-plussed, then grinned from ear to ear as we remembered the terror of those classes.

Cheam was a lovely small gentle school set in the most delightful grounds, and I didn’t know how happy I was there until I moved on to Radley.

Sport – Conkers, cars and dibs

Sport was everything at a boy’s school, both on and off the pitch. In the autumn term it was conkers. There was a whole language that went with this game. Conkers were collected from under Horse Chestnuts and a hole bored through their centre with a skewer. They were then threaded onto a string with a fat knot on its end. We took it in turns to strike the other’s conker with our own. I don’t know why the struck conker was much more likely to be destroyed than the striker, but that seemed to be the case. Each time your conker destroyed another, it took on its tally as well – the number of kills that the defeated conker had achieved. So, if a conker which had already destroyed 5 new conkers (a five-er) destroyed a ‘Three-er’ it became an “Eight-er’. If its outer brown layer was damaged it was called ‘skin-damaged’. If the central white meat had a split it was ‘deadly-damaged’. So the cry would go out. “Who will play a deadly damaged sixer?” and we would all descend on the doomed conker eager for its tally. However there were tricks for the unwary. Older boys pickled conkers from previous years in vinegar, or baked them in the bottom oven of the aga for days on end. These wrinkly specimens were indestructable. They could always destroy a fresh conker even when they were deadly damaged. So, James de Saumarez had a horrible wizzened deadly damaged several hundred-er (I cant remember the exact number) and we all soon learnt to steer well clear of it.

Playing conkers

Marbles, car-he, and dibs were also very popular once the conker season was over. The huge smooth polished parquet floors were ideal for marbles and for chasing our cars through under the desks and out into the corridor. Each different type of marble had a special name depending on its colouration and those which were rare were very valuable, being ‘swopped’ for up to twenty more common ones. The contents of your marble bag which swung from your belt was a great status symbol.

Marbles. Each pattern/size and colour has a name

Car-he required tough Dinky toys which had stiff axles and no self-steering. At that time Dinky toys were bringing out cars with little crystal lights (they didn’t light up) suspension and steering (if you pressed on one side of the car it turned the other way. These new cars were useless for car-he as they did not run fast and straight, and the key to success in this game was to hit your opponents car from a long distance. My mother knew that I had to have Dinky toys for school (it was on the check-list) but insisted on buying me a Rolls-Royce with lights and suspension (useless!). But my second car was an E-type Jaguar which had no add-ons and it went straight as a die!

Dibs was a game played with sheep knuckle bones. It is like Jacks which is played with a small ball and little crosses of metal. Just as in jacks there are a series of more and more complex manoeuvres which are performed in the time achieved by throwing one of the dibs in the air then catching it again before it hits the table. The rituals were complex with wonderful names which I have now forgotten, and at the end of term there was a Dibs competition when the best boys in the school would compete. I wonder if that is yet another game which has died out. The complexities of the game are well described in Wikipedia under knuckle-bones, a synonym for dibs.

Dibs/sheep knuckle bones

Every Saturday evening a film was shown. The favourites were ‘Pop-eye the Sailor man’ or wildly exciting adventure films like ‘Ivanhoe’. Those who had been been naughty that week were sentenced to detention during the film. They were obliged to spend from ten minutes to one hour (depending on the accumulation of bad marks) sitting at a desk, bolt-upright, looking straight ahead, arms folded in front of them, while down-stairs they could hear the film going on. I can think of no worse torture for a young boy. If the detention was longer than one hour then it was converted into a beating. Some crimes like talking after lights-out attracted an automatic beating, all the more painful because you were only in pyjamas.

Pranks

We got up to the usual pranks of climbing on the parapets at night, and having feasts in the grounds with bonfires and cider. The cider came in heavy brown glass bottles with stone toppers and we decided to see if we could make one explode by putting it on the fire half full of water. Nothing happened for a long time and we crept closer and closer. Hartley, a small boy with round milky-bar -kid glasses (who got bored easily) pushed his tuck-box really close. He was poking his head round the side when the bottle exploded. The fire was completely obliterated. Pieces of brown glass flew through the trees with wonderful whizzing noises. When the dust settled we found Hartley staggering around half-pleased and half-horrified. He was pouring blood. His ear had been split clean in half by a flying piece of glass. Even more fascinating was the lid of his tuck box which had huge chunks of glass embedded in it. A lucky escape for all of us, and Hartley’s tuck-box became a place of pilgrimage where the story of the cider bottle was told and retold. We were all beaten for this crime, and I certainly remember it hurting a lot. As I walked back down the corridor trying not to cry, I could feel deep welts in my buttocks. We must have been seriously frightened the head master. Certainly it was only luck that no one was seriously injured. Now that I think of Hartley, he appeared on my radar several times. Each week we were given an allowance of four ounces (125 grams) of tuck (sweets). We could choose these and in fact they were not graded exactly by weight but more by cost I suspect. A Mars bar was two ounces (half a weeks ration) but Aniseed balls were 20 to the ounce and lasted much much longer. However the most important part of ‘tuck’ was that it was the school currency. Marbles, dinky toys, you name it, were all traded in tuck, so many of us hoarded our tuck against the day when we might need to buy something big, or maybe we just hoarded it because we were middle class. Hartley went one step further. He set up a ‘tuck-bank’ where he stored any tuck deposited with him under lock and key. He packed it all very tidily and kept immaculate records of who owned what. If you invested in Hartleys ‘tuck-bank’ you received no interest but you were allowed to ask to inspect it. With great solemnity he would take you to his tuck box, unlock the huge padlock, and open it up to allow you to feast your eyes on the incalculable wealth that he controlled. I cannot think why we deposited tuck with Hartley except for the great thrill of seeing your tuck as part of a greater thing.

In my last year, a new head master insisted that we should do physical exercise outside before breakfast. One morning the master was late so we were left in our serried ranks larking about. Hartley, whose outward appearance with his Milky-Bar-kid glasses, belied a very extrovert interior suddenly decided that he would try to climb the corner of the 4 storey school building (an old manor house) using the offset bricks which ornamented each corner. Of course, we egged him on, but when he was about ten feet up, the master taking PT appeared and at once ordered him down. I think the combination of being the centre of attention for the whole school and the danger was too much for him, or was everything that he ever wanted – so he went on climbing, despite the increasingly anguished orders of the master. We were all hurried indoors and I never heard the outcome. We last saw Hartley heading for the parapets, and then we heard that he was ‘taken away’ by his parents later that day. I wondered what he ended up doing!

I loved cricket. I loved the sounds, the smells, the traditions, the discipline of a score book, BUT and it was a big but – I was useless at it. I could catch but I could not throw, I could not bowl and and I was hopeless at batting. I would have given anything to be as good as Sedgwick-Brown at cricket; he could bat bowl and throw effortlessly. Many years later, in my thirties, I agreed to play in a hospital match at my hospital in Essex. The words of the cricket master at Cheam, Colonel Shipway, once more rang in my ears. “Get your front foot to the bounce of the ball, and your bat tight against your pads. Drive forward!” I did, and I scored more than 20 runs including a couple of fours. That evening I went to sleep almost happier than I ever remember. Why on earth could I not have done that when I was young?

Cricket at Cheam

Radley

When I arrived at Radley I was 12, short, fat and very frightened. I spoke Latin pretty well and could read ancient Greek, and was ready to take GCE in maths, but I was not ready for Radley. It was a rough school and for the first year all twenty of the new recruits to the social (house) were in one room with a desk, a tuck-box, and a partition to separate us. At night we were in a dormitory of over 100 boys of every age, with only a low partition between you and the next room. As soon as lights went out there was pandemonium. To a new boy used to small dormitories of no more than eight this was something else. I had no idea of one half of what was going on and perhaps it was better that I did not. On top of that, beatings were carried out by the prefects in the central aisle. I just hid under the bed clothes and hoped for dawn.

One evening in social hall the prefect announced the death of President Kennedy. We were all ordered to look straight ahead for 30 minutes and reflect on the implications of this for the world order. My world order was centered around the social hall, and who was going to hit who next. I couldn’t see how President Kennedy or his successor was going to have much effect on that.

For the first two weeks at Radley, you had to learn off by heart everything about the school. Who could walk where, what colors did a Colt 1st team cricketer wear, and so on? I was quite unable to grasp this and failed the test. This made me into a permanent fag. When any prefect shouted for a fag, we all had to run and the last to arrive would be given the task (such as going to the shop to buy the perfect chocolate or something equally trite). As a permanent fag I had extra duties. I had to run the senior prefect a bath every morning (correct depth and temperature) and for Mr Nathan (another prefect with his own personal lavatory seat) I had to sit and warm it for him but on no account was I allowed to perform through it. Our house-master was old and discipline had gone to the dogs. At the end of a terrifying first year, a new housemaster arrived. Four boys were expelled immediately, four more were thrashed (quite literally) and the social settled down to a much safer, if closely disciplined, atmosphere.

I had arrived at the school with an Exhibition and was expected to get a scholarship at the end of the first year, but I had been completely unhinged by that first year and lost my Exhibition. I still got 13 GCSE but I was not doing well enough and was terribly unhappy.

Latin and Greek

I had to learn Latin and Greek at school up to GCSE. I was no good at either. Latin was still a requirement for entry to medical school, but Greek was simply gratuitous torture. I have to admit that later in life I did use my Latin once. A Portuguese ship’s crew all came in together to see me when I was a GP in Mombasa when their ship berthed. I spoke no Portugese and they spoke no English. In a moment of inspiration I started to ask them questions in Vulgate Latin the most simple form of this universal language, and the only kind I know. After each question they would confer together like a University quiz team, decide by consensus what I meant and then answer. My questions had to be simple and require only the answer ‘yes’ or ‘no’ but it worked. ‘Yes’ They did have a discharge from their penises and ‘yes’ it hurt to pee. Diagnosis made! However, I do question whether it was necessary to torture me for so many years with these dead languages when there are so many important living languages which need to be learnt. While I am banging on about what is taught in school, I really felt that we should have been taught a little about Modern History especially the Irish situation. It would have given me some perspective to the Irish troubles, the single most important domestic political issue in my life time. It cannot be beyond the wit of man to put together a module on issues that are important to our times. For example I think we should all be taught about the creation of Israel and the Palestinian situation. As one reporter explained, there is only 90 seconds on the news to present a story about anywhere abroad. If you are the correspondent for that area you know the geography and you know the history, so there is a danger that you assume that your audience does too. But do they? How many of us can draw the position of the Golan heights on a map, or describe the Balfour Declaration? If we are going to educate our children we might at least teach them what they need, not what the last generation were taught.

Sport at Radley

Sport was everything at Radley but you had to make the choice between being a dry Bob (rugby in the autumn, hockey in spring, cricket in summer) and a wet bob (rugby in the autumn then rowing for the rest of the year. I was hopeless at cricket so opted to be a wetbob). But really I was too small to row so I was made into a cox. This is a cold and miserable job. At least those rowing are taking exercise and keeping warm. There was also a lot of bullying and one of the worst was Radcliffe, the stroke of the boat I coxed. I lived in terror of him. Luckily I was not pretty as otherwise it would have been more than punches that I would have received. There was a strict hierarchy on the river. College (school) boats took priority over social (house) boats and eights took priority over fours.

One day we were in the house four and Radcliffe decided that in practice for the racing between the socials we would do a racing start and then row flat out 500 metres up the river. I remember him leaning forward and snarling in my face that I was to steer a straight course and on no account stop. I don’t know what he thought he was doing as the river was full of boats and we were one of the lowest on the pecking order. Anyhow off we went, and at about 200 metres going straight and well I saw an eight-ahead stop and start to turn around. It was the 3rd College eight and I was of no importance to them. But what they did not know was Radcliffe’s orders. I looked at him, and he was straining at his oar sublimely unaware of my dilemma. In the end, inertia won and we carried on. We hit the third eight at full speed just behind their cox (who was a good friend of mine). We cut the stern clean off and the eight sank where it was. Radcliffe could not believe what I had done, but I stuck firmly to the statement “you told me not to stop!” As we came into the dock, Radcliffe lent forward and snarled again in my face “If you say one word about what I said, I will kill you”. I was hauled before a court-martial of rowing masters but said not a word. I think they must have realized that there was more to this than met the eye, and I was banned from coxing ever again. Radcliffe, the skulking rat, never said a word to me or to anyone else about how or why this had happened. My first lesson in being scapegoated.

Bumps racing

The most exciting part of the racing year was bumps between the social eights which was run on exactly the same basis as torpids and summer eights in Oxford. We all started two lengths apart strung out down the river. When the gun went off, you rowed like hell to try to catch the boat ahead of you before the boat behind caught you. The key was the start. The boat had to be dead straight otherwise the cox would have to use lots of rudder, and the boat would slow. The back of the boat was held still by the cox holding a string attached to a peg on the shore, but the bow of the boat could only be held straight by frantic single strokes by oarsmen on one or other side. This was distracting and could ruin the start. By then I was a good swimmer and a confident diver. I knew that it did not take long for an eight to pass over you, so I volunteered to stand up to my chest in water holding the bow of the boat straight and steady. When the gun went I dived to the bottom of the river and stayed there until the eight had gone over me. It was very exciting and gave me great kudos in the social. However, I doubt that it helped our performance.

Despite being banned from coxing I still had to take exercise every afternoon. Radley always had something else on offer and just around the corner were the gravel pits where I could go sailing, fishing, and bird watching and escape the brutality of Radley. It has never ceased to amaze me that some of my colleagues who were sent to Radley or a similar school did the same to their own children. Did they have a lovely time there themselves, or is there selective amnesia, something similar to what occurs in women after childbirth? I had no money or desire to send my children to the Guantanamo Bay of Oxfordshire.

Bumps racing

Tribalism

The competition between the houses (socials) at Radley was intense and actively encouraged by the house masters. Most of this aggression was channeled into inter-social sports matches which were infinitely more fierce than inter-school matches. However even that was not enough to allay the intrinsic tribal aggression of small boys and I certainly remember one evening when we all piled out of our social to ‘attack’ another social, who had also somehow got themselves into a lather about us. Watching David Attenborough’s films of lemurs in Madagascar attacking other groups for no clear reason brought back to me the wild excitement of racing through the dark with a host of your fellow house-mates to attack another social who had now been designated ‘enemy’.

Looking back now there were all sorts of rituals that were presumably subconsciously designed to bond us. Before the prefect came into the social hall in the evening to supervise prep, the central table where he would work had to be polished. So the four most junior boys had to remove their gowns (we always wore gowns) and polish the table with these expensive items of clothing. The rest of the hall would egg us on so that when the prefect finally arrived we would be found in a frenzy of polishing. Order would then be called by the prefect and everyone would settle down well satisfied that one of the daily rituals had been successfully completed.

Chapel

Radley was a high-church school and so every effort was made to put us off religion by forcing us to sit through interminable rituals in church while there was a whole outdoors which we could have been enjoying. Services were in Latin and had psalm after droning psalm. They certainly succeeded admirably in putting me off. As the liberal attitudes of the 60s started to percolate into the school we started to rebel. We discovered that the organ pipes were situated under the gallery where some of us sat. As the masters could not see us in the gallery we could slide out of our seats and down between the stained glass windows and the seats to reach the organ pipe area. You could then ride the organ pipes like a horse. Each time that pipe’s note was played you got the most wonderful massage of your nether regions. A position on the longest 32 foot pipe was hotly competed for. Our house master wanted our social to be different from others and better in everything. So we were volunteered for the gallery where he insisted that he should be able to hear us singing louder than the rest of the school. We duly obliged but also managed to sing more and more slowly. The result was that over a couple of verses we could get a whole line behind and make a shambles of the service.

Chapel

Combined Cadet Force

We were also all compelled to take part in the Combined Cadet Force. The uniforms did not fit and this was clearly a marvelous opportunity to cock a snoot at authority. The military exercises were great fun especially as we were issued with thunder flashes. These explosive fireworks were a source of great pleasure, the best fun being to climb a tree and then drop one into a platoon of youngsters marching underneath. Once a year there was a General Inspection. Again, we managed to anticipate the antics described in Catch-22 and by marching more slowly than the band, managed to cause collisions and traffic jams between patrols. There was no one individual to blame for this corporate wickedness and even the prefects of Radley could not beat everyone, much as they would have liked to.

David Hardy

David Hardy, the biology master had spotted me even before I went into the sixth form where I was destined to do maths. I had not done biology ‘O’ level but had gone racing to him having seen a spotted and irridescent bird. At first he was bewildered by my extravagant description, then with a roar of laughter realised that I was talking about a common starling. From then on our friendship grew. He was a guru about natural history, knowing the names of, and something interesting about, every bird, flower, butterfly and moth. I was already a keen coarse fisherman, live baiting for pike and then fishing for trout on the school lake on flies that I had tied myself. I had been adopted by a group of farmer’s sons who took me beagling (the school had its own pack), fishing and poaching. I loved it. This world did not depend on how big you were or how hard you could throw a ball and it allowed me to explore some of the most beautiful parts of Oxfordshire, places that even now I come across by chance and am carried back to some of the happiest times of my childhood. The high point was when we caught a big pike on a Sunday morning having left the line out overnight in one of the gravel pits. We had sneaked down in our Sunday clothes straight after first chapel to see what luck we had. When we started to bring in this leviathan, we did not have a landing net, so I was delegated to jump in (in my Sunday suit) embrace this thrashing beast and haul him ashore. He was 12.5 lb, six times bigger than anything that we had ever caught. We carried him the mile back up to school and because he was still not dead we put him in one of the baths. The rest of the social queued to see our prize. Cribb then decided that we should stuff and mount the fish, so we set to work to skin it and make the relevant plaster castes. To my eyes it was completely perfect though I have no doubt that it was a shocking job. However, we did make one huge (quite literally) mistake. The glass eyes for stuffed fish came from a mail-order firm. When we received the catalogue we discovered that eyes for a 40lb fish were only slightly more expensive than those for a 20 or 10 lb fish. To our eyes, this was a forty-pound fish so we duly ordered the largest size. Of course, they were far too large and made the pike look thyrotoxic.

Caldwell’s poets

We were not the only group of misfits in the school. We had to play sport every afternoon and for some this was purgatory. I enjoyed Rugby and sculling, but for others, they were the worst part of the school program. On Wednesday afternoon we were supposed to do army training, but pacifism was already creeping in so there were options. One of the most macho-sounding ones was forestry, run by a large chemistry master with two great Danes and a passion for peonies. Those who did forestry would not say a word about what they did, but were all fairly feeble physical specimens. It was only after I had left the school that I discovered that Forestry was by invitation only. Dr. Caldwell, the master who ran it selected those of a more artistic or even poetical bent and took them far off into the forest at one end of the grounds. There they collected enough dry wood to make a bonfire and then sat around it reading their poems to each other. What an inspirational and paradoxical way of saving these more delicate souls from the horrors of a muscular school. Andrew Motion, the poet Laureate was, I believe, one of that group.

Field Trips

David took us on wonderful field trips to nature reserves like Bic’s bottom (for orchids) or Mimsmere and Havergate (for avocets). Just as Peter Scott describes in his biography I found my passion for killing wild-life being turned into a fascination in it.

Diving

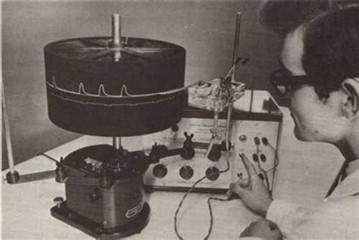

With David’s support, we started a sub-aqua club in the school, making our own wet-suits. In the next summer holiday I was out with my father in his boat when quite suddenly he went down into the cabin and brought out a huge box of anaesthetic equipment and before I could say a word he tipped it overboard. I was amazed and asked why he had done this. He explained that now that I had shown an interest in diving he did not want me going near the equipment that he and his friends had designed in the 50s for diving. He had read Jacques Cousteau’s books and decided to use obsolete anaesthetic equipment to build a diving set consisting of oxygen and a re-breath bag with a CO2 scrubber in it. Those of you into diving will know that this is one of the most dangerous systems which you can use. Pure oxygen is highly toxic at depth, and the CO2 scrubber is also highly unreliable. It was one of those moments when my estimation of my father went up in a great leap and a bound.

Trout fishing